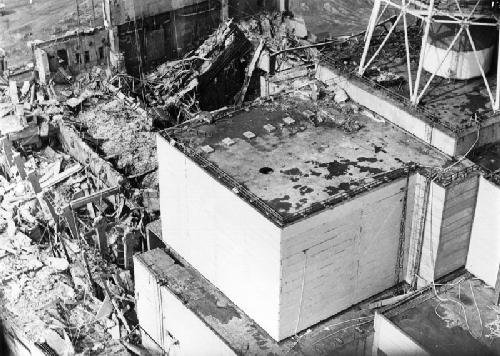

Accounts from Those PresentThese stories are adapted with permission from articles published in the Tri City Herald, March 6, 1994. They were written by Wanda Briggs, a reporter who was part of a delegation of American Engineers visiting Chornobyl, February of that year. Once Pripyat was a showcase. Today, it is the town that is no more -- a ghost town. It's 55,000 people once boasted theirs was the most progressive town in Ukraine, nation of 52 million. There was much to be proud of in Pripyat, the town built for workers at Chornobyl's four nuclear plants. It was a thriving, and modern, filled with schools, playgrounds, high rise apartments, restaurants, a music hall, a cultural center, an indoor pool and several athletic stadiums -- enough of the good things in life to compensate nuclear plant workers for their isolation. But on April 26th, 1986, at 1:26 am -- life changed forever. Today, Pripyat is surrounded by barbed wire.  It was business as usual that Saturday spring day in 1986. Larisa Weselska had worked at Chornobyl as a weld documentation specialist for eight years, but April 26th was her day off. She did her morning chores while her then eight year old son played ball in a nearby field. Another son, then two, played in a sandbox she could see from her kitchen window. By noon the town was filled with unconfirmed rumors that an accident had happened at one of Chornobyl's reactors. Still Weselska, was not worried. Surely, she believed, if something was seriously wrong, " the government, or someone would come and tell us." Nonetheless, she brought her sons into the house and closed the windows, which, like most in town that sunshine filled day had been wide open. "I could not believe, that when I first hear the rumor I had forgotten to do something as simple as close the windows." Rumors persisted and fears grew. Liza Aulina, heard those same rumors. She tried to call her boss, at the plant where she, too, worked as an engineer. " When I looked out from my eight floor apartment I knew I was seeing nuclear hell." "I could see that the whole block at reactor No. 4 was destroyed, there was no building on the reactor."  She joined friends and neighbors in the town square looking for answers. They got none for 14 hours. "Then we were told only there was a difficult situation at the plant," she said. The radio announced that there had been a minor accident." Still later, some 36 hours after the explosions at reactor No. 4, the people of Pripyat were told they had two hours to prepare to evacuate and that they would be gone from their homes for three days. Aulina was taken to one village, her then teenage daughter to another. They did not see each other for three months. Volodymyr Shovkoshytny, a Chornobyl plant engineer, was en route from Moscow, by train to his sixth-floor, two bedroom apartment in Pripyat when the Chornobyl explosion happened. He know nothing of the accident when he arrived home that morning. His four children, were there to greet him, and his wife Helena reminded him that they were to attend a wedding that day of a Chornobyl firefighter, one of the first to die of radiation sickness. "So many lives gone, so many people sick . So much sadness for my country," he now says. Shovkoshytny now President of Chornobyl Union International, and Aulina, executive director accompanied visitors from the US on a tour of the abandoned city. This was his first visit in five years, and her first since leaving. They wept at their memories as they led the group through the silent town. There were no people, no laughter, no dogs barking, no birds singing, no children playing - nothing. "I was once very happy here," said Shovkoshytny, who lived in Pripyat for five years. He pointed to an inside running track that was to have been opened on May 1st, 1986. "For that occasion, I had bought Adidas," he said. Nearby, a giant crane sits perched atop a multistory apartment that was being built when the town was abandoned. A Ferris wheel that never started is yet another stark reminder.  He showed the visitors through his apartment; its floors littered with glass, wallpaper peeling from the walls, socks covering a bedroom floor - left behind as the family rushed to escape. Most families in Pripyat expected to return home. They took what they thought they would need for three days. Each family stayed with strangers in first one village and then another. There were some people who refused to take in people from Pripyat, and soon - the word of the disaster spread - the people of Pripyat were ostracized. Eventually, most families were given 10,000 Soviet rubles to resettle, and now most of them call Kiev, the capitol of Ukraine, home. Liza Aulina Nuclear engineer, Liza Aulina felt personally responsible for the blast at the Chornobyl nuclear plant. "We all did, everyone who worked there. We were told it was our fault, and we believed it," she said. Aulina was not even working on the day that the 4th reactor exploded. Even so, "I had my duty" When the confirmation of the disaster came to Aulina and the other people then living in the nearby town of Pripyat, she tried first to call her boss and report for work. She could see from her eight-floor apartment the concrete housing that contained the reactor's core had been blown away. "I knew it was very, very bad." Her first thought was to get her teen-age daughter out of Pripyat and into a zone safe from contamination. "But there was no safe place... it was all around us. Only the KGB were safe. They had dosimeters and masks at the time for the disaster... no one else did," she said. Still, Aulina said, "My feelings of responsibility -- of guilt -- were greater then my fears. I had to return to Chornobyl." Ten days after the accident, Aulina returned. "It was beautiful at the entrance to the plant before the accident. There were colorful flowers and green trees. But already, when I returned, it was gray and ugly. On my first day back, I began to cry. I looked and saw what had happened, I realized what harm had been done to my country and to our people, and I wept buckets of tears." In the building next to plant No 4 where she had worked, "The windows were all blown out. It struck me to see the windows gone." Aulina moved into a work camp, Zeleny Mys, about a 40 minute bus ride from the destroyed reactor. Only people working in the clean up effort lived there. "There were 5000 of us at that time. We worked 10 hours everyday because there was a lot of work to do. It was necessary to clean everything. Then it was necessary to clean it again, and sometimes again," she said. There were 8 clean up workers in Aulina's crew. Five are now dead. For two months clean up workers received no pay. "Like me they thought they and their colleagues were responsible for the accident. We thought we had to work without money because it was our fault." Finally, a delegation of workers approached Aulina, because she was a woman, with a request. Their families were hungry. Would she talk to the bosses about their pay. Aulina agreed. "I explained we all felt to blame but that we had families to care for. We needed to buy food for them. They decided to pay us five times our regular pay - about 1000 rubles, which was a great deal of money for those times." Aulina left Chornobyl in August 1989 - nearly 3 and a half years after the accident. She finally realized, "This accident was a design fault. We stopped letting them blame us." Today Liza lives in Kiev, and is the executive director of Chornobyl Union International, where she works with a passion to improve the lives of all of those touched by this tragedy. They still all call her "Mom", even those who are members of parliament and have high government positions in the newly independent nations. She still does whatever it takes to get the job done, although her health is not good. She suffers with thyroid problems, but you always see her eyes filled with compassion - for the others. "We don't have time to worry about our own health - those of us who were there," she says. "We must do everything we can for the children now. Who will take care of them when we are no longer here?"

|